Do you have a mental illness? Why do some people answer ‘yes’, even though they haven’t been diagnosed yet

Mental illnesses such as depression and anxiety are very common, especially among young people. The need for treatment is increasing and prescriptions for psychiatric medications have increased.

These increasing prevalence trends are accompanied by a rise in public attention to mental illness. Mental health messages flood traditional and social media. Organizations and governments are developing awareness, prevention and treatment efforts with increasing urgency.

The growing cultural focus on mental health has obvious benefits. It increases awareness, reduces stigma and encourages help-seeking.

However, it can also be costly. Critics worry that social networking sites are causing mental illness and that the general unhappiness is caused by the overuse of diagnostic and «talk therapy» concepts.

British psychologist Lucy Foulkes argues that the increasing trends of attention and proliferation are linked. His «prevalence inflation hypothesis» suggests that increased awareness of mental illness may cause some people to misdiagnose themselves as having problems that are light or temporary.

Foulkes’ theory suggests that some people have a very broad view of mental illness. Our research supports this view. In a new study, we show that the concept of mental illness has expanded in recent years – a phenomenon we call «concept creep» – and that people differ in the breadth of their perceptions of mental illness.

Why do people self-diagnose mental illnesses?

In our new study, we examined whether people with broad perceptions of mental illness are, in fact, more likely to self-diagnose.

We defined self-diagnosis as a person’s belief that they have a disease, whether or not they received a diagnosis from a professional. We diagnosed people as having a «broad concept of mental illness» if they considered a wide range of experiences and behaviors to be problematic, including relatively mild situations.

We asked a nationally representative sample of 474 American adults whether they believed they had a mental health problem and whether they had received a diagnosis from a health professional. We also asked about other factors that may contribute to the population.

Mental illness was common in our sample: 42% reported having a current self-diagnosed condition, most of whom received it from a health professional.

Not surprisingly, the strongest predictor of the disease was relatively severe depression.

The second most important factor after depression was having a broad perception of mental illness. When their stress levels were the same, people with a broad perspective were more likely to report a current diagnosis.

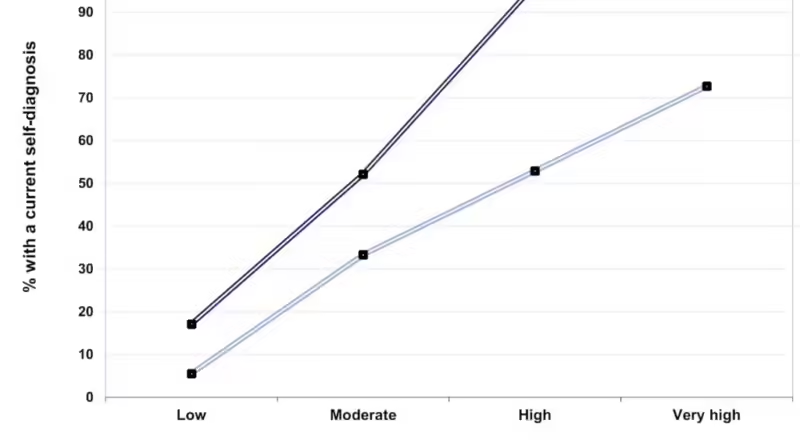

The graph below shows this effect. It divides the sample into stress levels and shows the number of people in each level reporting the current diagnosis. People with a broad spectrum of mental illness (the highest quarter of the sample) are represented by the dark blue line. People with a narrow view of mental illness (the lowest quarter of the sample) are represented by the light blue line. People with high mood swings were more likely to report having a mental illness, especially when their stress levels were high.

People with greater mental health knowledge and less stigma were also more likely to report a diagnosis.

Two other interesting findings emerged from our study. People who have self-diagnosed but not received a professional diagnosis have a broader perception of illness than those who have not.

In addition, younger and more politically progressive people were more likely to report a diagnosis, according to some previous research, and have a broader view of mental illness. Their tendency to hold these broad ideas partly explained their high test scores.

Why does it matter?

Our findings support the idea that broad concepts of mental illness encourage self-diagnosis and thus may increase the perceived prevalence of mental illness. People who have a low threshold for defining depression as an illness are more likely to self-identify as having a mental illness.

Our findings do not directly show that broad-minded people over-analyze or that narrow-minded people are ignorant. Nor do they provide evidence that there are broad concepts causes self-examination or ending with the real one increase in mental illness. However, the findings raise some important concerns.

First, they suggest that increased awareness of mental health can be costly. In addition to strengthening the knowledge of mental health can increase the chances that people choose their problems as pathologies.

Improper self-examination can have dire consequences. Diagnostic labels can become self-defeating and isolating, as people believe their problems are permanent, difficult to control who they are.

Second, unnecessary self-diagnosis can lead people with mild depression to seek unnecessary, inappropriate, and ineffective help. A recent Australian study found that people with mild depression who received psychotherapy got worse more often than they got better.

Thirdly, these effects can be very problematic for young people. They are responsible for the widespread perception of mental illness, in part due to the use of social media, and are experiencing mental illness at a high and rising rate. Whether broader perceptions of illness play an important role in adolescent mental health remains to be seen.

Ongoing cultural changes are encouraging more and more definitions of mental illness. These changes may have different fortunes. By getting to know mental illness they can help remove its stigma. However, by pathologising some types of daily stress, it can have unexpected effects.

As we battle the mental health crisis, it is important that we find ways to increase awareness of mental health without intentionally promoting it.![]()

![]()

This article is reprinted from The Conversation under a Creative Commons license. Read the first article.

#mental #illness #people #answer #havent #diagnosed